A bit of history of distillation

The early days of distillation remain somewhat unclear to this day. While remains of vases dating from the 2nd millennium BC have been found in Iraq and India, which appear to have been used to produce plant essences , the first written trace dates back to Aristotle in the 3rd century BC. He described how to desalinate seawater by evaporation. The first principles were established, but we were still far from distillation as we know it today.

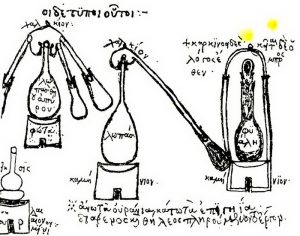

It was around the first century AD that the art of alchemists flourished in Egypt and that the first real distilling devices took shape. Used for medicinal purposes or for perfumery above all, they are part of the bases of modern chemistry. The Greeks described these devices precisely during the 3rd century, then the Arabs pushed the research even further by developing multiple inventions including " Al Ambiq ", and by producing various aromatic preparations then grouped under the generic name "Al Khôl" ("the fine thing"). Alcoholic drinks are called "Araq" ("sweat"), which is similar to the Latin etymology of distillation: "destillatio": "to flow drop by drop".

It was in the 13th century that Westerners took hold of these techniques to produce wine spirits , then used as remedies of all kinds, or as preservatives for wines, which gave rise to natural sweet wines such as Banyuls or Porto. In the 14th century, the appearance of devices allowing the cooling of condensation considerably improved the method, and distilled alcohols became consumer products.

The first distillations of sugar cane brandy certainly took place in the 16th century in Brazil, at the beginning of the colonization of the New World: it was Cachaça . This distillation of pure cane juice was already of an interesting quality, compared to what was done elsewhere in the Caribbean. At that time, neither molasses rum nor agricultural rum was produced there, but a coarse alcohol called tafia , made from the scum that overflowed from the boilers where sugar was made. In the middle of the 17th century, it was decided to valorize molasses by distilling it, which improved the tafia obtained, but it still did not have the best taste and was reserved for slaves and the poorest.

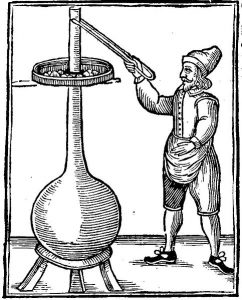

The rudimentary stills used to distill tafia (or " guildive ") were replaced by " pot-stills " at the end of the 17th century in the English possessions, and from the beginning of the 18th century in the French islands by Father Labat , who introduced Charentaise-inspired stills and double distillation . These techniques revolutionized tafia, which at the same time took the name of rum and which began to be increasingly coveted.

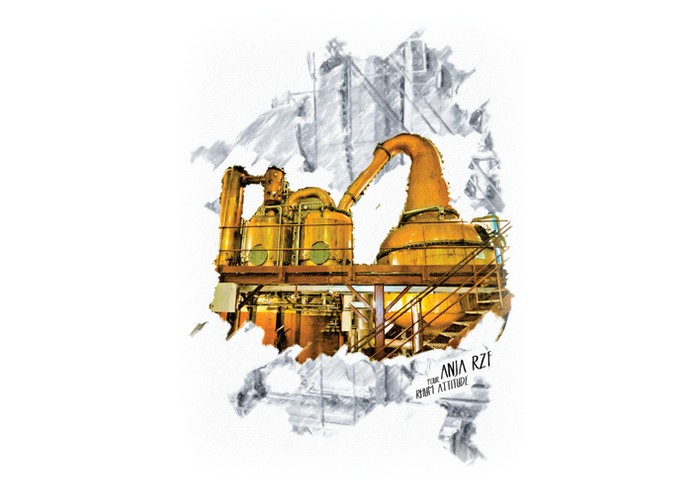

The advent of the distillation column in the early 19th century revolutionized the world of rum by introducing a much more efficient way of producing alcohol, leading to the large-scale industrial distilleries we know today. However, some distilleries have retained their artisanal know-how, whether or not they coexist with very modern facilities, and "primitive" rum distillations still exist in Brazil and Haiti , for example.

The principles of distillation

The basic principle of distillation is to separate the elements contained in a liquid according to their degree of evaporation. The still is heated to obtain the desired temperature and the vapors are recovered in a condenser so that they regain their liquid form. For example, ethanol evaporates at 78.4°C, while water becomes vapor at 100°C. The other components, and especially the aromatic components of rum , have different degrees of evaporation, and the art of the distiller lies in being able to select the desirable elements created during fermentation and get rid of the undesirable ones.

It is therefore not a question of obtaining the purest alcohol in the technical sense of the term, but of obtaining a rum which will have interesting aromas, more or less concentrated, heavy or light, depending on what one is looking for.

Distillation is an important step in the production of a rum, because in addition to the fact that it will separate the good aromas from the bad, it will also have an impact on the texture of the rum and its balance. A well-distilled rum will not cause any burning of the alcohol and will have, for example, a melting side depending on the quantity of glycerol that has been retained.

The different stills

Discontinuous distillation

This distillation is called “ discontinuous ” because it is done in batches: the still is loaded, distilled, cleaned, then reloaded and so on.

When the must (fermented cane juice or molasses) is passed through the still once, a distillate of approximately 25 to 35% alcohol is obtained. To further concentrate the distillate, it is passed through a second time, and this time the alcohol concentration is approximately 60%.

The progressive modernization of stills has made it possible to further increase this alcohol yield, in particular with the help of rectification devices which make it possible to "purify" the distillate. On the other hand, twisted stills make it possible to distil in a single pass, but always discontinuously, in batches.

Stills, whether Charentais, Irish or Scottish, are made of copper . This metal has a catalyzing effect that improves the chemical reactions in the still. The shape of the still and therefore the time the vapors spend in contact with the copper are therefore essential.

The selection of aromas is done in a way "manually", because the control of the distillation is in the hands of the person operating the still. After the heating has started, the distiller sees the "heads" flow, the first drops that will be separated because they contain dangerous substances such as methanol, but also undesirable aromas. Then comes the "heart", the "good heating". This is where an ideal temperature must be maintained to collect the best distillate, before arriving at the "tails", which constitute the vinasses devoid of alcohol but loaded with unpleasant aromas.

The alcohol content of the distillate follows an ascending then descending curve until the alcohol content of the must is exhausted.

Distillation continues

Continuous distillation is done in distillation columns. The principle is different because here we do not talk about heads or tails. The alcohol content of the distillate is constant throughout the operation which is no longer done by batch, but continuously.

Here's how it works: Steam is injected at the base of the column , and the wort is sent from the top. The wort goes down to the heart of the column, which is equipped with trays where the steam will meet the wort. The latter will " bubble " on the trays and the alcohol as well as the aromatic components will rise by evaporation.

The first trays are dedicated to concentration , from which an alcohol of about 60-70% will come out. It is interesting that this part at least is made of copper so that the catalysis reaction takes place, like a still. The bottom trays are called " exhaustion trays " and recover the heaviest components to evaporate them as well. The vinasses are evacuated at the bottom of the column.

To maximize the alcohol concentration, installations with larger columns or installations with several columns have been invented. The double column offers light distillates but retains the characteristics of the original must, while large multi-column installations are designed to produce very pure neutral alcohols.

The diversity of the rum world

The diversity of the rum world probably lies largely in the distillation processes. Some distilleries work with simple copper columns, the Creole columns . This is the case in Martinique, Guadeloupe , Guyana or some distilleries in Reunion (Savanna). These traditional columns are capable of producing very aromatic rums.

English-style rum producers are often equipped with pot stills and columns. In Jamaica , 100% batch distillation is most often preferred, to produce very heavy rums (Worthy Park, Hampden ). In Barbados, balance is generally sought by blending rums from columns and rums from stills (Foursquare, Mount Gay).

Some distilleries, such as in Antigua ( English Harbour ), use only a double steel column.

However, some large distilleries are equipped with the full arsenal, in order to offer rums with very varied profiles. This is the case of Demerara Distillers in Guyana, which has old stills, old and modern columns, as well as a multi-column installation.

Trinidad Distillers operates with a 5-column installation.

In the world of Latin American rums, most distilleries are large multi-column complexes that produce fairly light rums, but Diplomatico has a whole collection of apparatus ranging from antique pot stills to giant columns.

Among all this, there are exceptions, such as Appleton in Jamaica, which practices blending in the Barbados manner. And then there are hybrid stills , topped with a small column as at Rhum Rhum, or a larger one as at Mana'o or Manutea.

There are also cachaças which are traditionally distilled in a single pass in a still, or even the modified Clairins stills, etc. etc.

We have made a list of rums to discover according to their style, you will find it in our article on the production of rum and the different styles of rum .

It is this diversity that makes rum so rich (which also makes us sometimes get confused) and shows that each way of doing things has its uses. Heavy rums have their audience and are a major asset in blends , just like light rums which are also essential to mixology . It is not in any case, as we can sometimes see, a question of seeing distillation methods clash. Understanding these methods rather allows us to know what we drink and why we pay for it, and also allows us to compare what is comparable.

I think your articles made me fall in love with this field.

Thank you very much, we are very happy to share our passion and to make new followers 🙂

Really very interesting to read. Congratulations!!!

I still have a question about agricultural rum. It is noted that the cane is watered before pressing.

Is there any water added to the cane juice before fermentation? And what are the volumes?

THANKS

Thank you for this kind comment 🙂

The cane is often soaked in water to extract maximum juice during successive pressings, although this is not always the case.

In the absence of cane imbibition, when only one press is carried out, the juice is sometimes diluted in order to prevent too high a sugar level from harming good fermentation. The volume of this dilution is adjusted according to the volume of vesou and the measured brix.

The figure should be taken conditionally, but it seems to me that fermentation would become difficult beyond 18° brix.

Confirmation that Westerners first distilled cereals in the English-speaking islands (Ireland, Scotland, Wales) before using the process for grapes?

Hello, there is a question mark that remains in my mind concerning the different distillation methods. With the “traditional” European stills the first drops are thrown away because there is a presence of methanol. What about distillations carried out with a Creole column? thank you

Hello, and thank you for this question. Indeed, in a traditional still, we throw away the first drops and the last ones, respectively called “heads” and “tails” of distillation, the good alcohol being called “heart of heating”. However, we keep these heads and tails to put them back in the next distillation, which will allow them to be purified.

In the case of continuous column distillation, we could say that all these operations are carried out at the same time. That is to say, we are witnessing several distillations in a chain, each plate of the column being comparable to a still. In addition, the most volatile compounds (including methanol) can be reinjected into the column, by a reflux system, which purifies them considerably as the process progresses. In the end, only truly tiny quantities of methanol remain in the final product.